When it’s all over, one question remains: which side of history were you on? Daiyan Trisha remembers when she first watched All That’s Left Of You for the Malaysia International Film Festival (MIFFest) earlier this year—how she couldn’t stop sobbing, and the overwhelming emotions she felt afterwards. From then on, its director, Cherien Dabis, became her role model, and Daiyan waited for the right opportunity to spotlight the director.

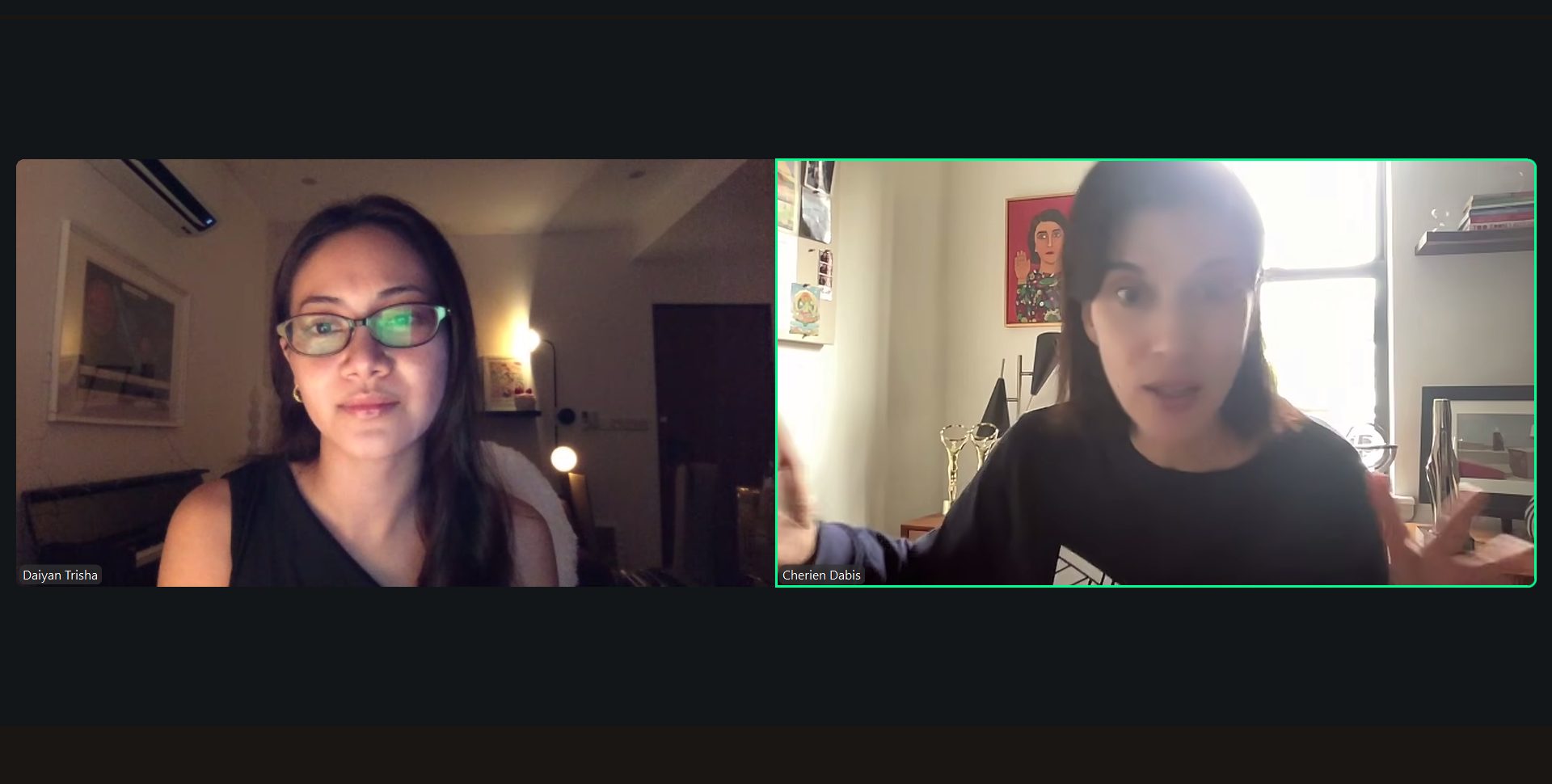

For her guest editorship at GRAZIA Malaysia this issue, Daiyan’s biggest wish was to interview Dabis. Catching the American-Palestinian director in between slivers of free time was challenging, but it finally happened. It was close to an hour of emotionally-charged, firsthand experiences spanning generations of grief from Dabis that could be felt through the Zoom video call—a reminder that we human beings are not that different, and not that far apart after all.

Your film, All That’s Left Of You, which you directed, produced, and starred in, has already won multiple awards and is also Jordan’s official submission for Best International Feature Film at the 98th Academy Awards. Were you surprised at how well this film has been celebrated, accepted, and recognised?

How does it feel, watching the reactions while screening it all over the world?

It’s been overwhelmingly positive. It’s such a gift to be able to share this movie—at this particular time—with the world, and it’s heartening that it’s being embraced and celebrated so much, given everything that’s happening. Having lived most of my life in the US, we’ve come such a long way with people’s awareness of what’s happening in Palestine. I’m just really grateful that I have this film because it helps me feel less powerless, especially with everything that we’ve been witnessing for the past two years.

So beautifully emotional. Let me put it this way: I’ve never gotten so many hugs in my entire life. People have been coming up to me after watching the film, saying, “You broke my heart and then put it back together.” It’s so beautiful! I feel like the movie is really connecting with people, opening their hearts and minds. It’s shifting perspectives and having a powerful effect on people everywhere.

What I love about cinema is that it speaks the language of emotions. This film, in particular, is a very emotional film. It’s speaking that universal language, bringing people together, to have this cathartic release. After what we’ve lived through and witnessed these past two years, it just feels so necessary. It almost feels healing, on some level, for people to watch the film and grieve along with this family as they watch them survive decades of political turmoil and personal loss.

I also feel like I’m only really recognising the opportunity right now with this film being released—the timing is so serendipitous. I never imagined when I wrote [this film] that I would be bringing it out into the world during a genocide. The world is becoming more and more polarised, but this film really seems to be bringing people together in a way that I hoped for, so that’s also really beautiful to witness.

Cherien Dabis

[Filming the movie] gave me something to focus on during an incredibly heart-wrenching time…to not just create any film, but literally about what’s happening, gave me such a sense of purpose that I was more determined than ever.

What were some of the most challenging processes of the whole filming?

We prepped the entire film in Palestine. I did a four, maybe five-month pre-production period with my Palestinian crew on the ground—we wanted to shoot in three different cities in the West Bank as well as Jaffa, Tel Aviv, and Haifa. We spent months prepping the film while Palestine was under occupation; we went in and out of checkpoints, airports, and we were interrogated, held—it’s not an easy place to film at, so that was already massively challenging. We were two weeks from shooting when the October 7th, 2023, incident happened. We had done all the work; we found all our locations, cast the entire film, and created all our props and set dressing—even my foreign crew had just arrived on October 1st. When it happened, we realised that we weren’t going to be able to shoot the film in Palestine or move around—suddenly it became too dangerous for us to stay. Honestly, it was one of the biggest challenges in my life, because the film entered a total crisis. We had a financial crisis, a logistical crisis—we didn’t know where to go or if we’d be able to continue making the film. We had to evacuate the crew, and I had to flee as well. It was devastating because we had to leave our entire Palestinian crew behind; we didn’t know what was going to happen to them, if we’d be able to return, or if we could bring them with us if we shot elsewhere. It took us many weeks to figure it out and raise more money. Essentially, we had to start pre-production from scratch, which is unheard of. No director preps a movie twice! We ended up shooting it mostly in Jordan—the Palestinian refugee camps north of Jordan—and Cyprus and Greece. I found myself looking for Palestine everywhere but in Palestine. It was a surreal, crazy experience.

What was it like for you to separate like mind and heart matters emotionally and rationally? You had to be professional, but also face all of these issues.

It was really intense. In some ways, part of the reason why I’m so grateful to have the film is because it gave me something to focus on during an incredibly heart-wrenching time. To not just create any film, but literally about what’s happening, gave me such a sense of purpose that I was more determined than ever. I thought, I have to make this movie now. This movie needed to come out yesterday. It was so intense, this feeling of, I have to do whatever it takes. We have to get this done. We remained so steadfast and focused, and that’s eventually how we got the film done despite not having the resources. I wasn’t taking no for an answer because I felt like what I was doing was so much bigger than me.

Last September, I saw that Mark Ruffalo and Javier Bardem both signed on to be executive producers for All That’s Left of You. How did you feel having such big names supporting your work?

That was such an amazing moment. It was such a huge win for the film. I’m such a massive admirer of both of them, not only because of their extraordinary talent, but also their huge hearts. They’re amazing human beings who have always been on the right side of history and spoken up in defence of justice and humanity. It was so thrilling to have them come on board, commit as executive producers and help with our Academy campaign, press, and raising the visibility and awareness of the film throughout the world. It makes me so happy seeing them walk the red carpets and getting every piece of screen time to talk about it.

What made you want to create the story from the whole three generations angle?

I was inspired by my father in many ways; my relationship with him and what I observed growing up. My grandfather, father, and my siblings and I all have differing opinions about Palestine: what happened, what’s happening, and what should happen. I always found it interesting how trauma can sometimes skip a generation. My father is Palestinian from the West Bank. He was exiled in 1967, so he automatically became a refugee. It took him many years to get foreign citizenship just to be able to visit his family and homeland—the only home he’d ever known. I grew up watching his heart break more and more with time, over what was happening. I also watched his health deteriorate as he became more obsessed with Palestine and the injustice of what was happening, to the point where he didn’t talk about anything else.

He had heart attacks when he was young, you know. I wanted to show how political events impact people, because we don’t think about that. Even though we’re not directly in the line of fire, I was amazed at how much my father was impacted just living in the diaspora and watching the events from afar. We went back and visited a lot when I was a kid. I watched my father being harassed and humiliated at borders and checkpoints. I saw how political events completely changed him over time. And then, I watched how my identity almost formed in opposition to him because I saw how much he suffered holding on to Palestine. I wanted to find a different way; I wanted to let go and not focus on the past but on the future. How can I let go of this pain and suffering? What can I do with this inheritance of trauma? How can I try to channel it into something that was perhaps even beneficial for the people?

That was what got me thinking about making a film about how one family—and multiple generations of one family—are impacted by these ongoing political events that we’ve been reading about for decades. I was also really motivated to put a human face on the headlines. We’re so used to Palestinians being nameless, faceless numbers—but I was always so struck by how little people knew about our emotional lives and how we’ve been affected by decades of upheaval and political events that have been imposed on us.

At the end of the movie, a poem by Egyptian poet Muhammad Hafez Ibrahim was portrayed on the screen. Does this poem hold a personal place in your heart?

I love this poem, and I really like the poet. Basically, the poem opens and closes the film. It’s in the 1948 part of the film where we first hear it. I had to obviously choose a poet that was popular during that period—and Hafez Ibrahim was, in 1940s Palestine and all over the Arab world. He was known as the poet of the Nile. But he was also known as the poet of the people, because he wrote about ordinary people’s struggles, and I love that. This particular poem is so beautiful because it’s a tribute to the beauty and richness of the Arabic language.

I wanted to honour the Arabic language in the way the movie honours Palestinian humanity, resilience, culture, and language. So I felt it was an appropriate poem for the film, and a beautiful way to bookend the film. It also works on different levels of meaning, because while the poet’s intention is about the Arabic language, he could also be speaking about any one of us. He could be talking about human beings or Palestinian people, or the treasures within our hearts. I found the poem to be deeply layered, rich, and meaningful—really evocative.

This story first appeared in the November 2025 issue of GRAZIA Malaysia.

READ MORE

November 2025: The Paradox of Being Daiyan Trisha

Land As Memory: The Palestinian Artists Reclaiming Landscape Through Art

Threaded in Identity: Meet The Palestinian Designers Weaving Stories Through Fashion & Jewellery