In the heart of Central Java, where dawn mist curls around volcanic peaks, stands Borobudur; not merely a temple, but a mountain of wisdom carved from stone. Built in the 8th century by the Sailendra Dynasty, it rose at a time when Buddhism mingled with Javanese cosmology, creating something uniquely local. Each tier of Borobudur mirrors both the Buddhist journey to enlightenment and the Javanese belief in harmony between the human, natural, and spiritual worlds.

Over centuries, Borobudur was forgotten, swallowed by jungle and volcanic ash—yet the wisdom it embodied endures. To walk its spiralling path today is to trace an ancient way of understanding the world. In its silence, Borobudur continues to speak of ancestors, of earth, and of the Javanese truth that the sacred lies in the harmony we create here on earth.

Centuries later, this same wisdom lives on in the nearby villages, in the hands of the ibu-ibu who weave and dye fabrics. Their craft, passed from mother to daughter, carries the same spirit of harmony and mindfulness that Borobudur embodies. They work with natural dyes drawn from the earth, guided by seasons, soil, and patience. In their woven threads, as in the temple’s stones, endures the indigenous Javanese wisdom that true enlightenment lies not in transcendence, but in living gently and consciously within the world.

It was this very wisdom, the intelligence of the land and its people, that moved Rolex Awards Laureate Denica Riadini-Flesch to found SukkhaCitta—a sustainable “farm-to-closet” clothing brand—nine years ago. Travelling through rural Java, she saw that the ibu-ibu who carried generations of knowledge in their hands were being left behind by the modern industry. Their dyes, once made from indigo leaves and tree bark, were being replaced by synthetics. Yet what Riadini-Flesch saw in their work was the same living philosophy that breathed through Borobudur, the belief that every act, when done with awareness and purpose, can be sacred.

SukkhaCitta was born as a way to reclaim that indigenous wisdom and give it new life. By reconnecting craft to its roots, soil, water, and community, Riadini-Flesch turned sustainability into something personal. Each piece of clothing made by the ibu-ibu in the village is not just fashion, but a reflection of patience and a reminder that true beauty comes from goodness.

Return to Source

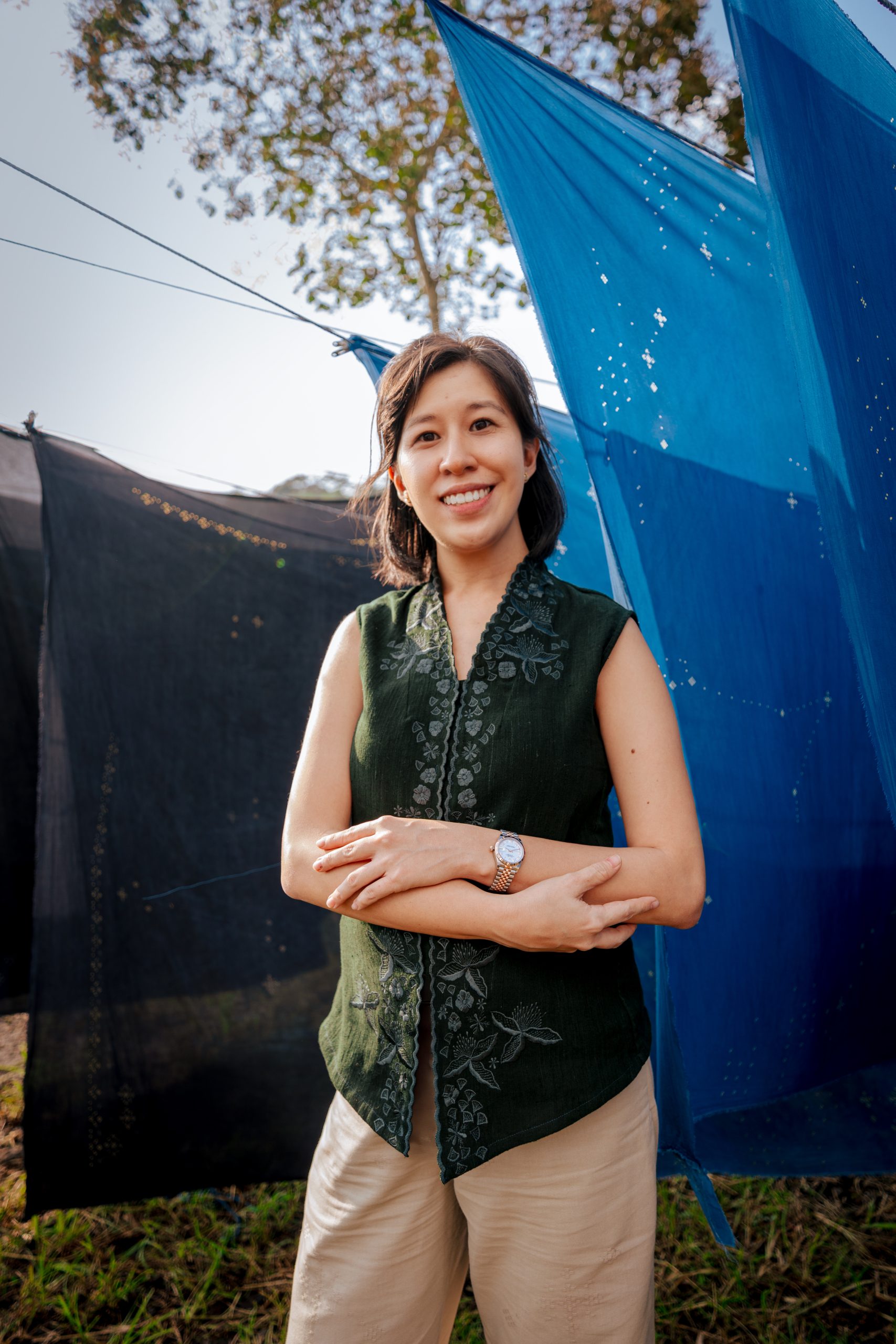

On a sunny August morning this year in Central Java, we arrive at Rumah Sukkhacitta. Rolex Awards Laureate Denice Riadini-Flesch, wearing an inky black sleeveless vest and beige trousers, welcomed us to a humble hut which now doubles as the workshop where women—young and old— learn the ancient batik craft. The land, some 300 miles east of Jakarta, brims with shrubs and trees that grow cassava, coffee, and cocoa. But it’s the forest floor that’s brought Riadini-Flesch to this corner of her home country. Beneath the shade of banana, papaya, and coconut trees, she’s nurturing a revolution in the form of hundreds of vibrant indigo plants.

Today, SukkhaCitta partners with hundreds of Indonesian farmers and artisans on Java and neighbouring islands like Bali, Flores, and West Timor. Riadini-Flesch’s work and her outfit that morning tell the same story: garments dyed with natural indigo, woven by hand, shaped not by machines but by the rhythm of human care. As she stands among the trees, she gestures to the leaves around her. “This,” she says, “is a fashion forest.”

Indigo, she explains, is both metaphor and method: a plant that embodies transformation. Traditionally, the indigo that thrives in Ambarawa needs full sun, which would have meant cutting down trees. Instead, Riadini-Flesch introduced Assam indigo, a hardier varietal that flourishes in the shade, allowing the forest to remain intact. The result is a thriving ecosystem where crops, soil, and community sustain one another. “The land becomes alive again,” she says. “And so do the people.”

This philosophy: to regenerate rather than extract, forms the spine of SukkhaCitta’s “farm-to-closet” model. Every piece of fabric is grown, spun, woven, and dyed in the villages. Cotton fibres are hand-spun and woven on manual looms; the batik patterns are drawn by hand with molten wax before being dipped into vats of colour made from plants. The entire process takes months. Yet in that slowness lies intention and meaning.

The Spark of a Movement

Nine years ago, Riadini-Flesch was far from this life. Trained as an economist in Jakarta, she believed progress was linear, measured by perpetual growth and GDP charts. After a stint at the World Bank, she began travelling across Indonesia to document rural poverty. That was when she met three batik artisans in a small village in Java. They told her how their mothers had once used natural dyes, indigo, mahogany bark,and mango leaves, but had since switched to cheap chemical ones that burned their lungs and poisoned their rivers. Their craft was fading and their dignity eroding. That encounter was a turning point. “It made me realise,” she recalls, “that without knowing it, I was part of the problem.”

Riadini-Flesch returned with a different kind of ambition; not to scale, but to restore. With just $2,000 in savings, she began working with the ibu-ibu, paying them living wages and reviving old methods of natural dyeing. Her first creation was a simple bandanna, hand-dyed indigo, patterned with butterfly motifs named Kupu, the Indonesian word for butterfly. It symbolised metamorphosis, for both the artisans and herself.

Over time, trust grew. What began as a partnership evolved into family. The ibu-ibu began teaching Riadini-Flesch the subtleties of their craft, how to read the weather, when to harvest dye leaves, and how to let the cloth breathe. One of them once told her, “It isn’t blood that flows through our veins. It’s hot wax.” That line, Riadini-Flesch says, still moves her to tears.

Living Mandalas

In a way, to walk through a SukkhaCitta village today is to step into a living mandala. Just as pilgrims once circled Borobudur’s terraces to cleanse the mind, the ibu-ibu move through their daily rituals, stirring vats of indigo, tracing wax on cloth, tending cotton fields with the same mindfulness. Every act, from planting to weaving, forms part of a cycle of care, patience, and renewal.

Their work draws directly from indigenous farming systems like tumpang sari, an age-old Javanese technique that plants multiple species together to nourish one another.

Cotton grows alongside corn for shade, chilli to repel pests, and peanuts to fix nitrogen in the soil. It’s a living ecosystem, the agricultural equivalent of Borobudur’s stacked terraces, where each level supports the next.

SukkhaCitta’s Mama Kapas program reintroduces heirloom cotton, regenerating degraded soil and reviving biodiversity. Since its founding, the initiative has restored more than 120 acres of land and prevented millions of litres of toxic dye wastewater from entering rivers. But numbers tell only part of the story. The real change is more human. Women who once inhaled toxic fumes now breathe fresh air; families who once leased land now own it. “The opposite of poverty isn’t wealth,” Riadini-Flesch says. “It’s dignity.”

Bridge Between Worlds

Riadini-Flesch works at the intersection of worlds between the ancient and the contemporary. Her project is not about nostalgia, but continuity. In reweaving the threads of craft, land, and community, she’s redefining what progress can look like in the modern age. In 2023, her efforts were recognised globally when she was named a Rolex Awards for Enterprise Laureate, an honour that celebrates innovation in the service of humanity and the planet.

“Artisans and farmers are the missing link to solving the climate crisis,” she says. “When indigenous wisdom, regenerative farming, and economic dignity come together, we don’t just reduce harm; we rebuild the future.” Her impact now stretches far beyond Java. SukkhaCitta’s garments have been worn by cellist Yo-Yo Ma, Coldplay’s Chris Martin, and oceanographer Sylvia Earle—proof that clothes made from humble village plots can resonate globally. The brand’s clothes, priced at a premium, are transparent in their making; each tag traces the journey from seed to garment. But for Riadini-Flesch, the real luxury lies in awareness. “Clothes won’t change the world,” she says, “but the people wearing them will.”

Back at Rumah SukkhaCitta, younger generations are now learning to merge traditional craft with ecological literacy and entrepreneurship and soon via a new app that Riadini-Flesch’s team is currently developing. The average age of artisans is dropping, a sign that the youth are finding new value in ancestral knowledge.

Riadini-Flesch’s journey is far from complete. Through her Rolex Award, she has a huge opportunity to take SukkhaCitta’s mission even further. “The amazing thing about Rolex is that they give you a mic,” she says. “They let you speak about what you truly believe in, to inspire others to do the same. It’s in Rolex’s DNA to support pioneers.” With this support, she plans to triple the number of craft schools. By 2030, her goal is to impact 10,000 lives and regenerate 1,000 hectares of land. She’s also launching an app with SukkhaCitta’s digital curriculum—so women across Indonesia, even in the most remote areas and speaking different dialects, can learn and build better futures.

Threads of Continuity

Today, SukkhaCitta is both an enterprise and an ecosystem, a model for how business can align with indigenous wisdom rather than erase it. Riadini-Flesch’s mission is not to romanticise the past but to prove that the future can be built on older, wiser foundations. “We think sustainability is something new,” she says. “But for generations, our ancestors already knew how to live in balance. We just forgot.”

In the end, Riadini-Flesch’s story, like Borobudur’s, like the ibu-ibu’s, is not about fashion at all. It is about remembering what it means to live with awareness, to work with the earth rather than against it. In one of Riadini-Flesch’s posts, she mentioned that Ibu Srikanthi once shared a phrase that changed her life: Urip Iku Urup (we live to bring light).

And in the shaded radiance of indigo leaves, in the steady hands of the ibu-ibu, in the small acts of weaving and making, that light continues to grow.

This story first appeared in the November 2025 issue of GRAZIA Malaysia.

READ MORE

How Rolex Perpetual Planet Initiative Pushes The Limits of Human Knowledge

Rolex Perpetual Planet Initiative Continues To Safeguard the Poles, Mountains and Forests

Rolex Perpetual Planet Initiative Creates Change at Kep Archipelago Hope Spot